Why AI can’t yet generate business process diagrams

Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) has become the standard for documenting how organizations work. But creating and maintaining accurate process diagrams requires expertise that many companies simply don’t have. Large Language Models (LLMs) could change this. Describing a workflow in plain language and getting a proper BPMN diagram back. The technology seems ready, but current LLMs can’t reliably produce valid, standard-compliant outputs. We explored why.

Introduction

Large Language Models like ChatGPT and Claude can now generate structured outputs directly from everyday language, not just text. This opens up an obvious possibility: automating the creation of professional process diagrams, potentially closing the gap between business experts and technical modelers (Li & Toxtli, 2024).

The need is clear. In today’s interconnected economy, transparent and standardized workflows are essential. BPMN 2.0 provides a uniform way to represent business processes that work across platforms. It enables communication between business and IT departments, supports process analysis and automation, and drives continuous improvement (Object Management Group, 2011).

But there’s a problem. Despite the theoretical promise, practical implementation reveals substantial obstacles. Traditional single-model prompting rarely produces valid BPMN outputs, especially for complex processes.

Why do LLM’s struggle with BPMN generation? What are the key challenges that must be overcome before we can rely on automated process modeling?

Why process modeling is not as easy as it seems

BPMN 2.0 has become the international standard for business process modeling. Its graphical notation bridges business stakeholders who design processes and technical teams who implement them, supporting the entire lifecycle from documentation through optimization to automation (Dumas et al., 2018).

Organizations across every sector rely on BPMN. Healthcare institutions document patient care pathways from admission to discharge. Financial services map compliance workflows. Manufacturing companies coordinate supply chains. Public administrations standardize citizen services.

Yet most organizations struggle to create accurate BPMN documentation. The problem: manual modeling requires deep knowledge of both the business domain and the notation itself.

Consider a hospital emergency department. A clinical expert understands triage, diagnostics, treatment decisions, and discharge protocols. But translating this into valid BPMN means understanding gateways, events, sequence flows, and pools. Should a treatment decision be an exclusive or parallel gateway? When does a subprocess become necessary? How do you model exceptions? Research shows people working with BPMN often introduce errors due to insufficient understanding of notation semantics and business domains (Haisjackl et al., 2018).

This documentation gap blocks digital transformation. Organizations can’t optimize or automate processes they haven’t properly documented. But they often lack personnel who understand both the business domain and BPMN modeling, and hiring such experts is expensive and time-consuming.

Why LLMs cannot reliably generate BPMN

BPMN diagrams aren’t just visual representations, they’re formally structured XML documents that must follow strict syntactic and semantic rules. A typical business process model contains dozens or hundreds of interconnected elements: tasks, gateways, events, sequence flows, pools, lanes, and artifacts. Each element has specific attributes and must maintain valid relationships with others.

The rules are unforgiving. A sequence flow must connect exactly two flow nodes. Gateways need appropriate incoming and outgoing connections based on type. Boundary events must attach properly to activities. Even minor violations render the entire XML file invalid and non-importable by BPMN tools.

This structural rigidity contrasts sharply with natural language. Minor grammatical errors rarely prevent comprehension. In BPMN generation, there’s no tolerance for approximation, the output either works or it doesn’t.

Complex processes exceed context limits

Even state-of-the-art LLMs operate within finite context windows. When handling large or detailed process descriptions, models lose critical information about earlier elements while generating later portions. This becomes particularly problematic for complex workflows with multiple parallel branches, exception handlers, or subprocess hierarchies. The model must maintain awareness of all previously generated elements to ensure proper connectivity and avoid duplicate identifiers.

Knowing BPMN isn’t the same as building it

LLMs can be trained on BPMN specifications, tutorials, and example diagrams. They possess theoretical knowledge of BPMN concepts and can accurately describe various elements and their usage. But theoretical knowledge doesn’t translate into practical generation capabilities.

Creating valid BPMN XML requires precise coordinate calculations for element positioning, correct namespace declarations, proper ID management across hundreds of elements, and adherence to layout conventions. LLMs lack the iterative refinement loops that human modelers use. A human expert incrementally creates a diagram, adjusting positions and connections based on visual feedback. An LLM must generate a complete XML structure in a single forward pass without the ability to “see” and correct the result.

Every run produces a different diagram

Even more fundamentally, LLMs are generative models, they produce different outputs each time they execute. Ask the same LLM to generate a BPMN diagram from identical input twice, and you’ll get two different results. This non-deterministic behavior is inherent to how LLM models work.

For process modeling, this creates a serious problem. Organizations need stable, reproducible process documentation. A procurement workflow documented today must remain consistent tomorrow. But LLMs will generate different element IDs, different layouts, potentially different interpretations of the same process description on each run. This makes version control nearly impossible and undermines the fundamental purpose of process documentation: creating a stable reference that the organization can rely on, analyze, and improve over time.

Human modelers produce consistent results because they work from a stable mental model and intentionally maintain continuity. LLMs generate from probability distributions, making consistency across executions fundamentally difficult to achieve.

Professional diagrams need professional layout

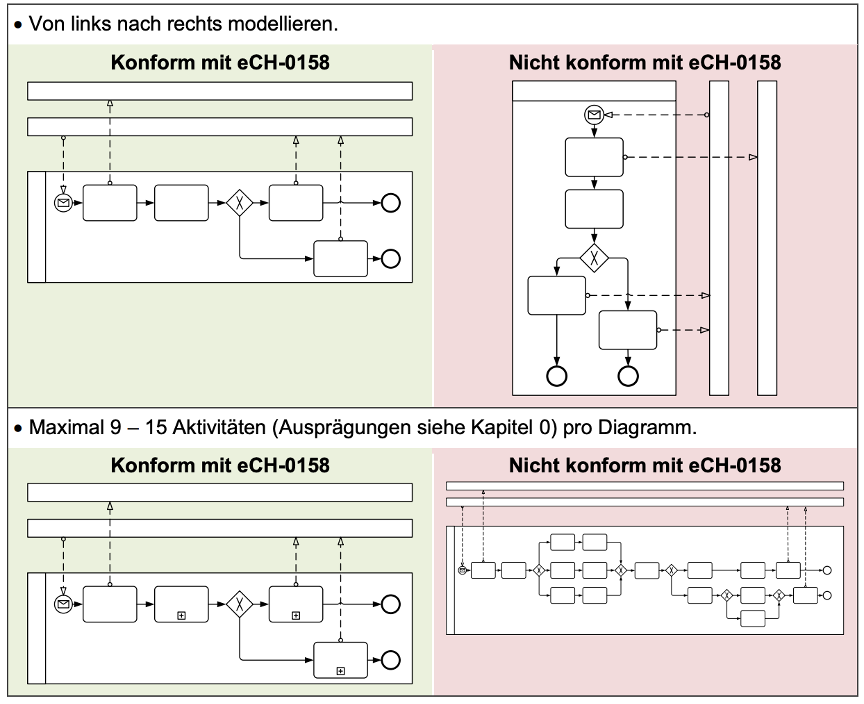

Beyond structural validity, professional BPMN diagrams must meet visual standards for readability. Standards like eCH-0158 (eCH, 2020) specify conventions for element spacing, flow direction, alignment, and annotation placement.

Figure: Examples of compliant and non-compliant BPMN modelling according to the eCH-0158 standard (source: eCH-0158).

LLM-generated diagrams frequently produce layout problems: overlapping shapes that obscure labels, crossing sequence flows that create confusion, inconsistent spacing, and misaligned elements that violate professional standards. These visual deficiencies may not prevent technical validity, but they significantly reduce practical utility.

The Path Forward

Automating business process diagram generation could democratize process documentation and accelerate digital transformation. But current LLMs face fundamental challenges that prevent them from reliably producing valid, standard-compliant BPMN outputs.

The complexity of BPMN’s structural requirements, the limitations of context windows for large processes, the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical generation capability, the inherent non-determinism of generative models, and the difficulty of automated layout all contribute to the unreliability of single-model approaches. Related work confirms these limitations across multiple diagram types and application contexts, consistently finding that human validation remains necessary to ensure output quality.

Addressing these challenges requires moving beyond simple prompting strategies toward architectural innovations that can decompose complexity, enforce constraints, ensure reproducibility, and validate outputs systematically. The development of such approaches represents an important direction for future research on AI-supported process modeling.

References

Dumas, M., La Rosa, M., Mendling, J., & Reijers, H. A. (2018). Fundamentals of business process management (2nd ed.). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56509-4

eCH. (2020). Standard for business process modeling eCH-0158 (Version 1.2). eGovernment Switzerland. https://www.ech.ch/de/ech/ech-0158/1.2

Haisjackl, C., Soffer, P., Lim, S. Y., & Weber, B. (2018). How do humans inspect BPMN models: An exploratory study. Software and Systems Modeling, 17(2), 655-673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10270-016-0563-8

Li, W., & Toxtli, C. (2024). Automating automation: Using LLMs to generate BPMN workflows for robotic process automation. In World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, and Applied Computing (CSCE 2024) (pp. 221-229). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-86623-4_18

Object Management Group. (2011). Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) Version 2.0. https://www.omg.org/spec/BPMN/2.0/

Create PDF

Create PDF

Contributions as RSS

Contributions as RSS Comments as RSS

Comments as RSS

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!